Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica)

Many people have fond memories of honeysuckle plants... the sweet aroma of its flowers and the sweet taste of nectar sucked out of the flowers during the summertime.

However, Japanese honeysuckle can be highly invasive, outcompeting native plants and girdling young trees.

Japanese honeysuckle was brought over from Asia as an ornamental plant and is still sold and planted in gardens for ornamental value or planted for the browsing of horses. Unfortunately, once planted, this species can quickly spread both by seed and via their root systems. Once it spreads, it can outcompete native plants for nutrients and grow up small trees, blocking out sunlight for the trees and plants below. It will grow in disturbed areas, such as floodplains, which may be one of the reasons we see it at our sites.

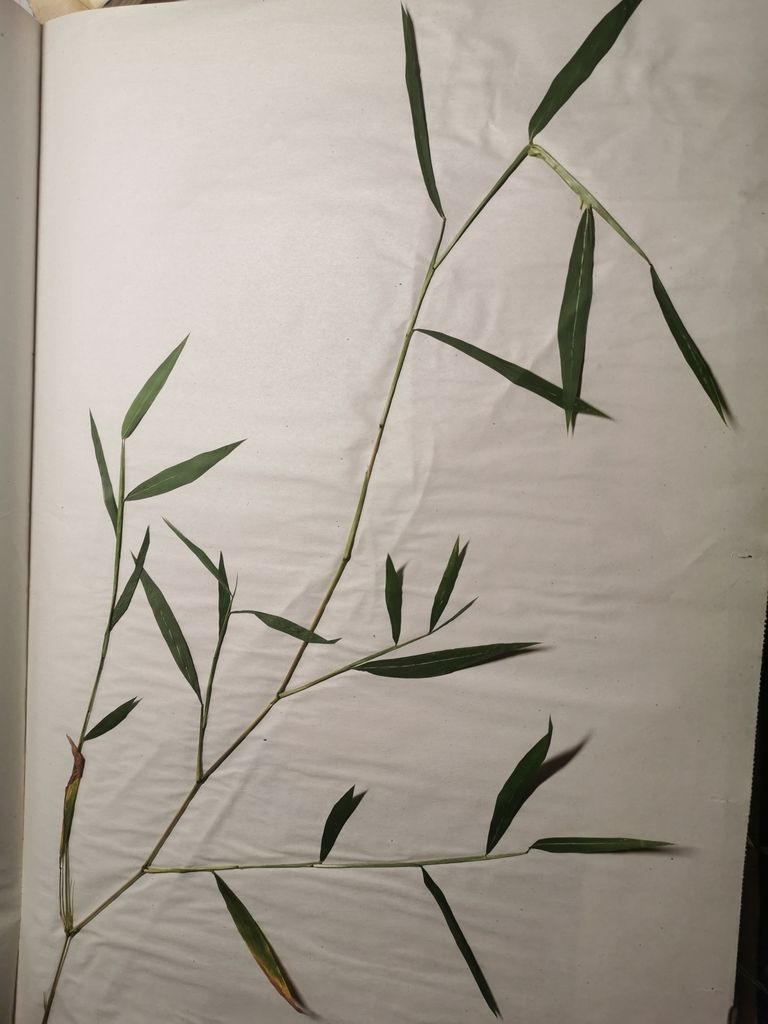

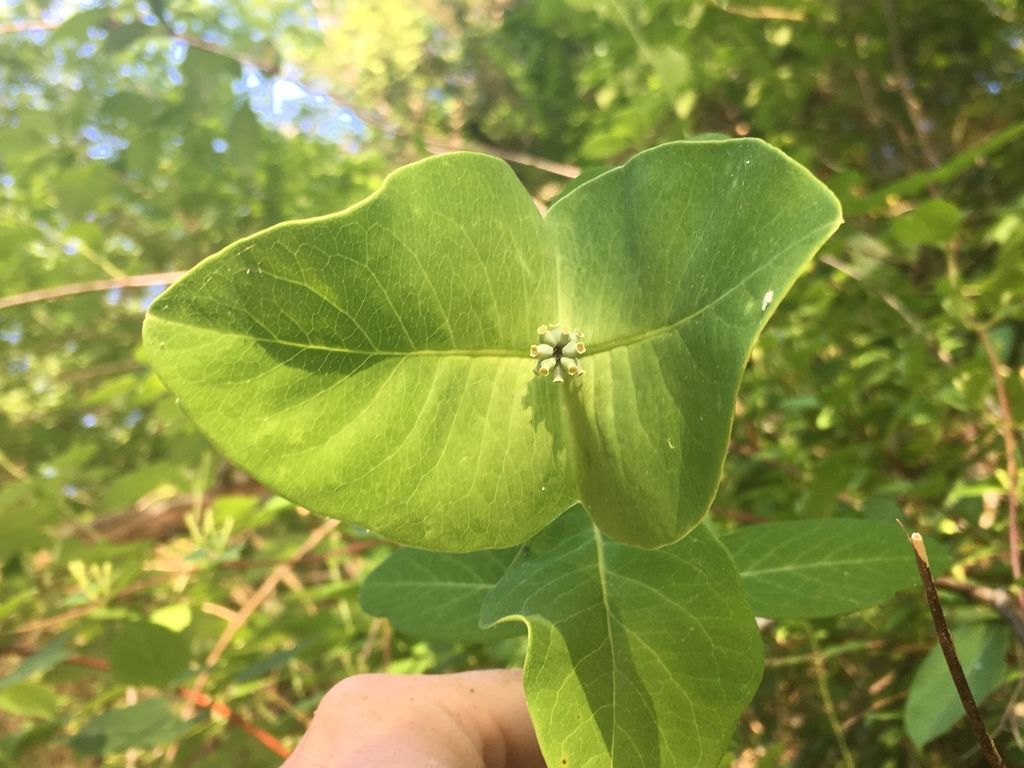

When you can’t smell its white and yellow flowers, Japanese honeysuckle can be identified by it’s small (1-2.5 inch), oval, entire (smooth), green, opposite leaves with pale undersides. Younger leaves, may lobe.

The leaves grow along a thin, hairy, reddish to brown vine. The vine can grow along the ground or vertically up small trees. On older plants, the vine can get up to 2 inches in diameter and develop a splintery quality.

In fall it fruits with small, black berries.